Meteorologist clears the air about Point Peninsula ‘weather bubble’

Zachary Canaperi/Watertown Daily Times

The west end of Point Peninsula projects into Lake Ontario, as viewed from the cabins at the Westcott Beach State Park Overlook. The peninsula, according to some locals and charter boat captains, is the center of a weather bubble. Zachary Canaperi/Watertown Daily Times

CHAUMONT — Over the years, a strange fog has settled in over eastern Lake Ontario. A culmination of stories has blended with the sciences and muddied the air, resulting in mysterious clouds of local lore.

The lake’s northeastern corner is home to geographical anomalies, magnetic disturbances, shipwrecks and disappearances, leaving lots of questions, but very few answers.

However, one of these unknowns — the existence of a weather bubble around Point Peninsula — may finally have its answer.

Gene Bolton, captain of Sunken Treasures Fishing Charter, Henderson Harbor, said that he watched the phenomenon occur during snowstorm event on Jan. 15. He lives on the plateau above Westcott Beach State Park, which gives him great visibility for storm watching.

“I can see all see all the way over into Canada, across the shipping lanes and across Point Peninsula, all the way over into Kingston on a clear day,” Bolton said.

“When that storm rolled in Monday,” Bolton recounted, “you could see a full-blown white out everywhere to the southwest, and then from Point Peninsula north was all clear, and it was like glowing — it was pretty cool,” he said.

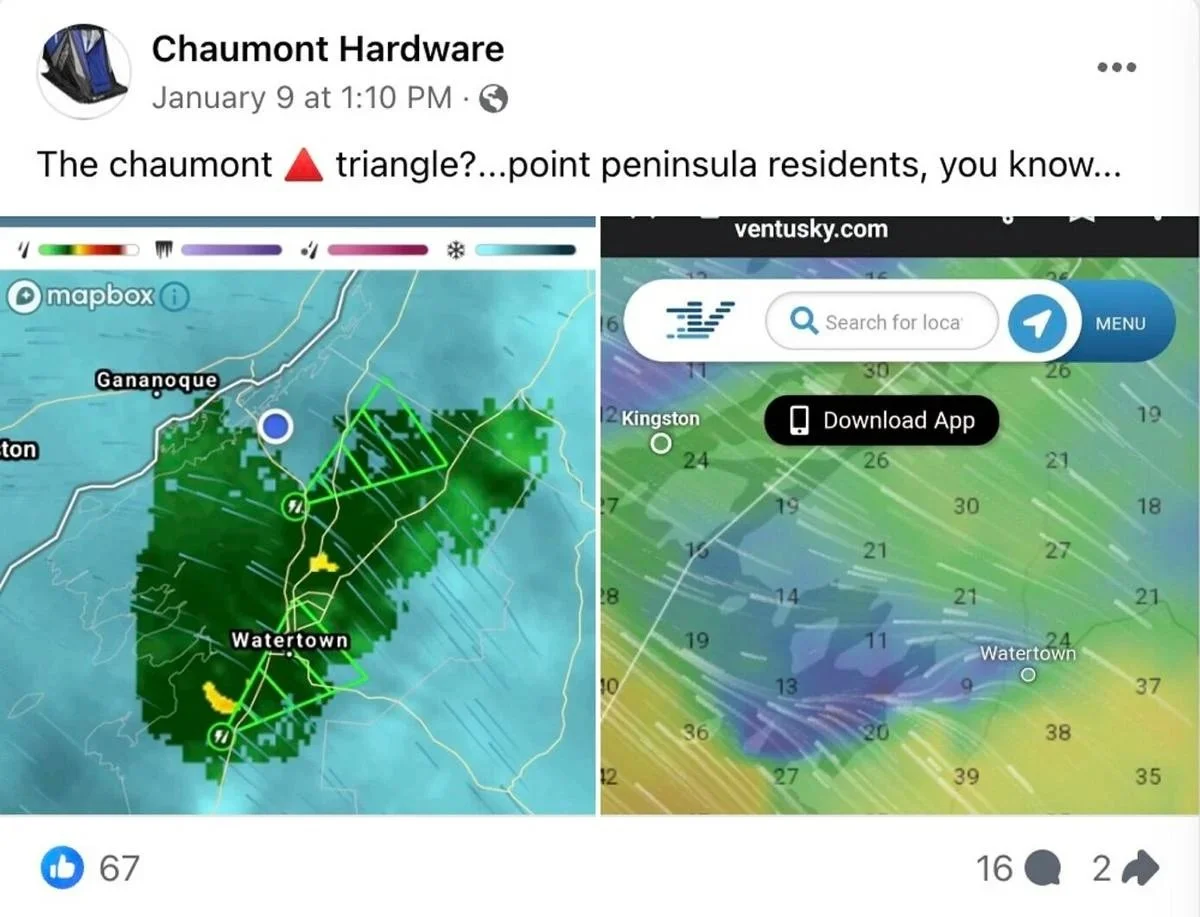

The weather bubble has also been a topic for discussion among locals on Facebook. The Chaumont Hardware Facebook page, which locals use as a source of both weather and fishing reports, shared a photo on Jan. 9 that prompted sixteen comments.

A Chaumont Hardware Facebook post that prompted several comments regarding a Point Peninsula weather bubble. Watertown Daily Times

The post was a screenshot of radar imaging, showing a clear section around Chaumont and Point Peninsula during a storm.

“I call it our bubble on Point Peninsula,” one commenter said.

“I can sit in my deck in the dumber (summer) and just watch the storms go around the point!” another commented.

Sandy Blevins, Chaumont, who captained Gone Fishin’ Charter for 20 years, said that captains are well aware of the weather pattern.

“The storm fronts will separate when they get to Stony and Galloo islands, and half will go up the river, and the other half will go south of us. And it’s not just a winter phenomenon; it goes on in the summer, too,” Blevins said.

The west end of Point Peninsula projects into Lake Ontario, as viewed from the cabins at the Westcott Beach State Park Overlook. The peninsula, according to some locals and charter boat captains, is the center of a weather bubble. Zachary Canaperi/Watertown Daily Times

But according to Blevins, nobody knows why this occurs.

“I don’t think anybody has any idea why. Maybe the river, being wide open, is a draw for some of it. Other than that, nobody can really say why it happens. That’s the way it is,” she said.

The explanation could be difficult to see in waters murky with the region’s many peculiarities. For example, the region is home to the “Marysburgh Vortex,” the Great Lakes’ version of the Bermuda Triangle. The term was coined by Hugh F. Cochrane, author of “Gateway to Oblivion,” a 1980 book that documents mysterious happenings in a three-sided region in eastern Lake Ontario. The two northern points are in Canada — Marysburgh Township to the west and Kingston to the east — and its southern point is in Oswego.

On May 28, 1889, the puzzling disappearance of the eight-man crew of the timber schooner, Bavaria, may have been one of the first wrecks to set the tone for future mariners.

According to newspaper clippings at the time, during a storm the Bavaria broke free of its towing barge, the Calvin. The Bavaria stayed upright and didn’t drift very far from the barge, but the captain of the Calvin made a shocking discovery when, only minutes later, he checked on the crew and found that they had all vanished.

After the storm, the Bavaria was found beached on the shore of Galloo Island, completely intact, leaving people to wonder why an experienced crew would abandon a perfectly good ship for angry seas that could swallow them up. The crew was never found.

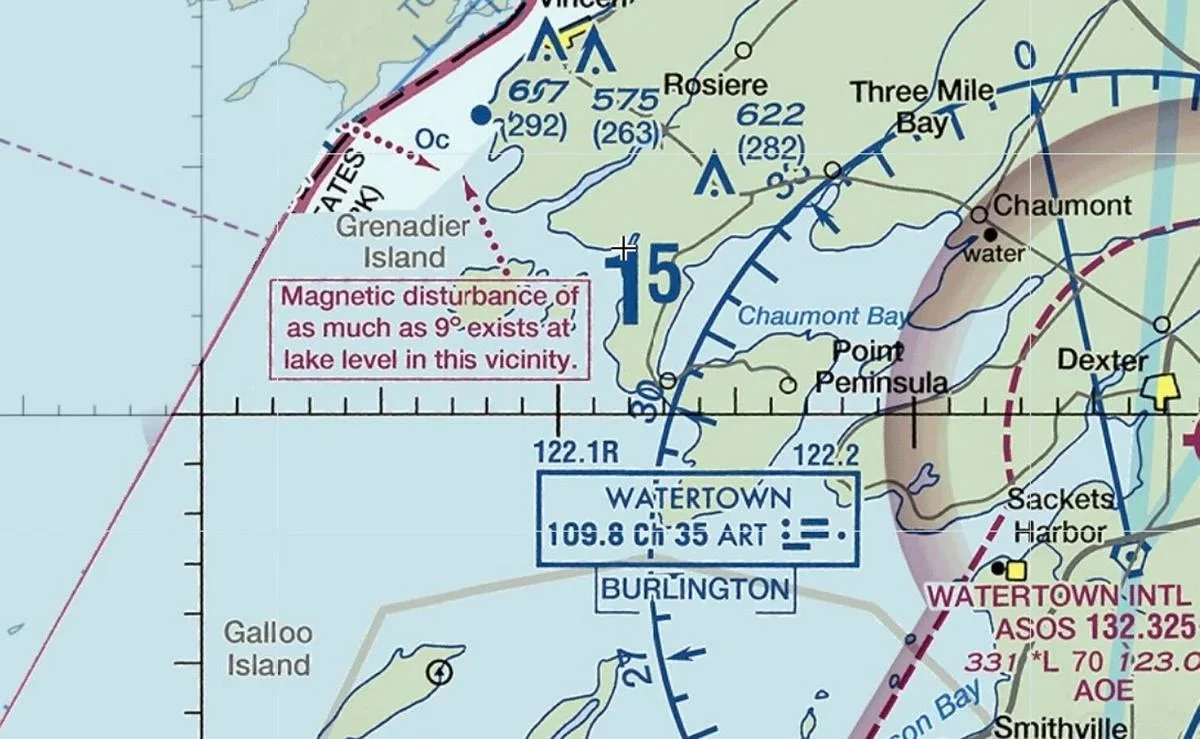

An aeronautical chart warning of a 9-degree magnetic disturbance by Charity Shoal in Lake Ontario. Watertown Daily Times

An aeronautical chart warning of a 9-degree magnetic disturbance by Charity Shoal in Lake Ontario. Watertown Daily Times

The wrecks in Lake Ontario kept coming. The David Swayze Great Lakes Shipwreck File documents the location of 5,000 wrecks across all the lakes. A 2021 Global News analysis found that almost half of Lake Ontario’s shipwrecks, 270 of them, occurred in the far eastern end, in a zone that takes up less than a quarter of the total surface area.

Charity Shoal, a crater roughly 3,000 feet in diameter, sits six miles southwest of the entrance to the Saint Lawrence River. Charity Shoal lighthouse was installed in 1935 after ships wrecked into its shallow, rocky rim.

The Charity Shoal lighthouse as the sun sets on Aug. 27, 2022. Alec Johnson/ Watertown Daily Times

The shoal is believed to be a meteor impact crater, and evidence suggests that mineral deposits from the meteor may be the cause of a strong, localized magnetic disturbance. Aeronautical charts mark this anomaly, with a warning that states: “Magnetic disturbance of as much as 9° exists at lake level in this vicinity.”

Mark Wysocki, a seasoned meteorologist and professor of Atmospheric Sciences at Cornell University, Ithaca, is not intimidated by triangles of any kind, or meteor craters.

Diving right into the question, the researcher looked at several factors in the eastern Lake Ontario and the north country region, making an initial analysis of the weather bubble reports. His assessment found that they are far from folklore.

The two most important considerations are topography and wind direction.

When a storm passes through the area, the air will either sink or rise over the topography, depending on the direction it is moving. This will then determine the level of precipitation that occurs.

Wysocki believes that both a southerly flow and a northeastern flow will create what he calls a “hole in precipitation.”

“The wind pattern is associated with these storms,” Wysocki explains. “Let’s say you have one coming in from Buffalo, New York, and it’s heading up towards Montreal. As the storm is approaching that region, you tend to get more of a southerly flow, either southeast or south-southwest type of flow. Now, that means that the air will be coming from New York state, somewhere around Pulaski. As the air comes from the south it’s going to have what we call downsloping. In other words, it’s going to come from more of the elevated area south of Oswego and Watertown and down the slope of land. As the air sinks, it gets compressed due to pressure differences. That heats the air up. When you heat the air up, you are also going to dry the air. This would show up very nicely on radar.”

Wysocki is quite sure that this is the reason people on the peninsula see storms apparently avoiding them.

“So, when we get these southerly flows, I would say that it’s not folklore,” he said. “I would say it really has to do with the fact that the air is coming down from the land down to the shore of Lake Ontario, and as it sinks it is going to be warmed, and it will dry out the air at the same time. So, any precipitation falling in that air will start to evaporate, and you will either end up with one, less precipitation, or two, no precipitation.”

According to Wysocki, this would also account for the “glowing” clear sky that captain Bolton witnessed.

“It is not only what happens at the surface, it also happens aloft, so you may also see reduction in cloud cover at times,” he said.

Northeastern movement will have a similar effect, because those storms are also moving down the topography, which warms and dries the air.

Under a more direct westerly flow across the lake, you will not see this decrease in precipitation, but rather an increase, because the air will be forced upwards when it reaches the land — hence the region’s lake effect snows.

Due to a lack of official weather observation in Chaumont, Wysocki encourages boat captains and others who find themselves inside the precipitation hole to take note of the wind direction and report their findings. Reports can be emailed to zcanaperi@wdt.net.